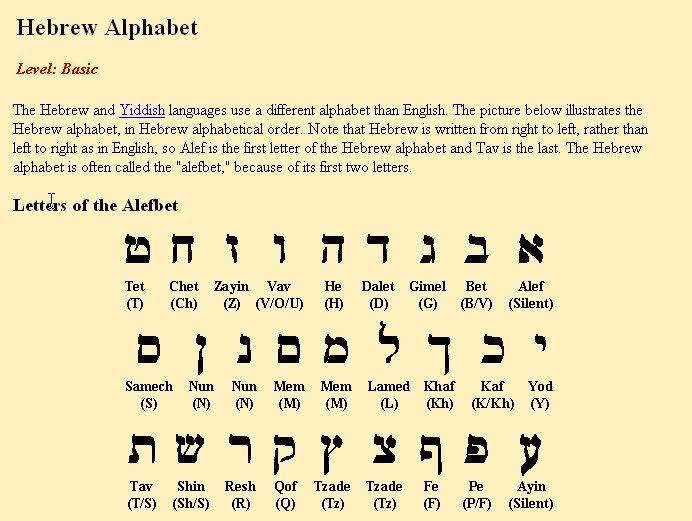

There are not any J's or W's in Hebrew1

to be cont...Strong's Exhaustive Concordance is almost a necessity for gaining a deeper insight into the original languages. Notice in the Hebrew dictionary of Strong's No. 3050, the entry "Yahh," a contraction for 3068 [the Tetragrammaton, the Sacred Name].

"Yah" is found in HalleluYah, meaning "praise you Yah." Also it appears in names like Matthew: MatthewYah, Isaiah: IsaYah, Jeremiah: JeremYah, Zephaniah: ZephanYAH, Nehemiah: NehemYAH, and other names ending in "iah." Yah means "I exist," "I am," "I create," or "I will be or bring into being."

Yah is the poetic or short form of His Name found to have survived translators in Psalm 68:4 of the King James Version. It is the prefix of the name Jehovah as found in Strong's Exhaustive Concordance which is most interesting and shows the fallacy of the name Jehovah.2

J

The symbol (from the German Jahvist; Yahwist in English) used by German OT scholars and followed internationally to denote one of the sources of the Pentateuch, which uses Yahweh for the name of God. It was probably written in the south of the country in the 10th (or 9th) cent. BCE, though a few recent OT scholars think it might even be post-exilic. J is characterized by anthropomorphisms (e.g. Gen. 8: 21) but above all records the faithfulness of God to the promises he made to the patriarchs.

"J" A Dictionary of the Bible. W. R. F. Browning. Oxford University Press, 1997. Oxford Reference Online. Oxford University Press. 25 May 2008

W

23rd letter of the English alphabet and a letter included the alphabets of in several W European languages. Like f, u, v and y, it was derived from the Semitic letter vaw (a name meaning hook). The Greeks adopted vaw into their alphabet as upsilon. The Romans made two letters out of upsilon Y and V (see V; Y). The V was first pronounced as a modern English w and later as a modern English v. Norman-French writers of the 11th century created the modern form of the letter by doubling a u or v to represent the Anglo-Saxon letter wynn, which had no counterpart in their alphabet. In modern English w is what phoneticians call a lip-rounded velar semivowel, made like the oo vowel sound in zoo but functioning as a consonant, as in war and swing. Like y, it sometimes has a vowel quality, but usually only when used with another vowel as in new, now or flow. It is silent in such words as answer and wring (words in which it was originally pronounced). In some words introduced by the combination wh, the w is today not sounded (as in who, whom and whore). But in which, what, white and whisk, a voiceless form of w is used. However, in some dialects of English, and all of those in England, this voiceless w is regularly being replaced by ordinary w.

"W" World Encyclopedia. Philip's, 2005. Oxford Reference Online. Oxford University Press. 25 May 2008

W, w

[Called double-you]. The 23rd LETTER of the modern Roman ALPHABET as used for English. The Romans had no letter suitable for representing the phoneme /w/, as in OLD ENGLISH, although phonetically the vowel represented by v (as in veni, vidi, vici) was close. In the 7c, scribes wrote uu for /w/, but from the 8c they commonly preferred for English the runic symbol wynn ([wynn]). Meanwhile, uu was adopted for /w/ in continental Europe, and after the Norman Conquest in 1066 it was introduced to English as the ligatured w, which by 1300 had replaced wynn. Early printers sometimes used vv for lack of a w in their type. The name double-u for double v (French double-v) recalls the former identity of u and v, though that is also evident in the cognates flour/flower, guard/ward, suede/Swede, and the tendency for u, w to alternate in digraphs according to position: maw/maul, now/noun.Sound value In English, w normally represents a voiced bilabial semi-vowel, produced by rounding and then opening the lips before a full vowel, whose value may be affected.Vowel digraphs (1) The letter w commonly alternates with u in digraphs after a, e, o to represent three major phonemes. Forms with u typically precede a consonant, with aw, ew, ow preferred syllable finally: law, saw, taut; dew, new, feud; cow, how loud. (2) When the preceding vowel opens a mono-syllable, silent e follows the w: awe, ewe, owe (but note awful, ewer, owing). (3) Word-finally, w is almost always preferred to u (thou is a rare exception), but w occurs medially quite often (tawdry, newt, vowel, powder), and the choice of letter may be arbitrary (compare lour/lower, flour/flower, noun/renown). (4) In some words, digraphs with w have non-standard values: sew, knowledge, low. Final -ow with its non-standard value in low occurs in nearly four times as many words as the standard value in how. (5) In the name Cowper, ow is uniquely pronounced as oo in Cooper. (6) Final w in many disyllables evolved from the Old English letter yogh () for g, as in gallows, hallow, tallow, bellows, follow, harrow, borrow, morrow, sorrow, furrow (compare German Galgen, heiligen, Talg, Balg, folgen, Harke, borgen, Morgen, Sorge, Furche).

"W" Concise Oxford Companion to the English Language. Ed. Tom McArthur. Oxford University Press, 1998. Oxford Reference Online. Oxford University Press. 25 May 2008

Works Cited

1Quoted: 1997 Mrs. Michael (Ann) Weiner The Congregation of Shomair Yisrael http://shomairyisrael.com

2 2007 Yahweh’s Assembly in Yahshua

www.YAIY.org

Oxford University Press, 1998. Oxford Reference Online. Oxford University Press. 25 May 2008

Supported by The Rockefeller Foundations